Sediment study finds growing number of chemicals in Great Lakes

The Great Lakes are essential to life in many ways. They contain one fifth of the world’s fresh surface water and are one of the most diverse ecosystems on Earth. More than 3,500 plant and animal species call the lakes home, some of which are found only in Lake Superior, Lake Michigan, Lake Huron, Lake Erie, and Lake Ontario. The lakes are a source of drinking water to tens of millions of Americans and Canadians, and they are critical to the economies of both countries as they support manufacturing, farming, transportation, tourism, recreation, energy production, and much more. UIC researchers have found that human activity has led to an increase in chemicals in the Great Lakes.

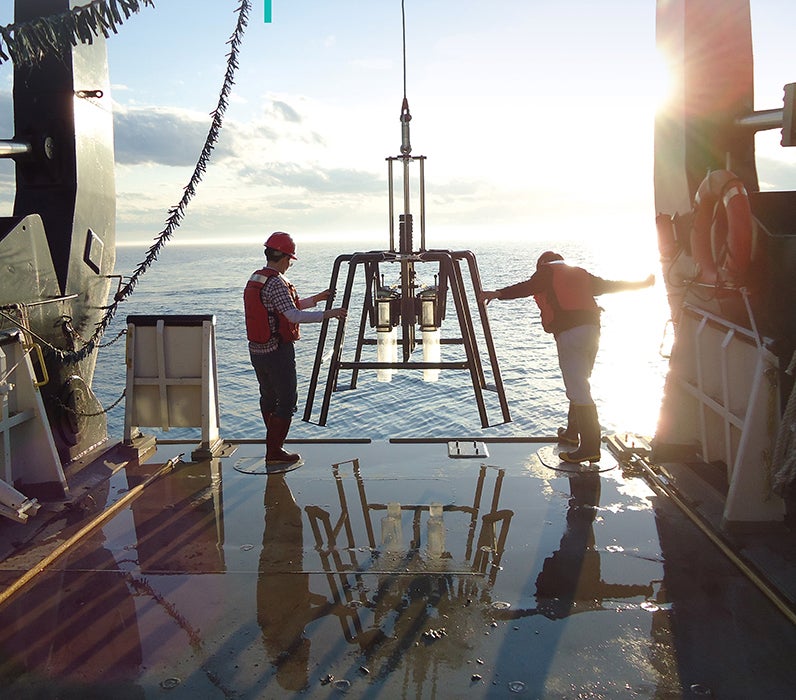

Karl Rockne, a professor in civil, materials, and environmental engineering and the associate dean of research in the COE at UIC, has been researching the Great Lakes for many years, and his most recent paper “Polyhalogenated Carbazoles in Sediments of Lower Laurentian Great Lakes and Regional Perspectives” in the journal ACS ES&T Water covers the chemicals he and his team have found in the lakes. Emeritus UIC School of Public Health Professor An Li was the principal investigator of the Great Lakes survey project and lead author.

“Our overall objective was to look at sediments and look for various micropollutants in the sediments,” Rockne said. “The reason for focusing on sediments is that they are kind of like a library that holds a record of what has happened in the past.”

Throughout the years, Rockne and his team have seen natural chemicals in the sediment and found these chemicals are decreasing. However, newer testing has uncovered new chemicals that are anthropogenic, which refers to environmental change caused or influenced by people.

Through dating, they know that this new class of chemicals started in the 1980s and has been increasing greatly.

“We’re talking about hundreds of tons of this material and it’s similar now to compounds that we’ve been concerned about for decades. They’re clearly increasing with time, and they appear to be anthropogenic,” he said.

What appears to be the case is that these compounds might be byproducts of certain types of dye production, and a result of chlorine production. Researchers have looked at former or current chlorine production facilities and are finding these compounds in the soils. Some other sources appear to come from pharmaceuticals, semiconductors, and herbicides.

“These types of chemicals are clearly known to disrupt ecosystems. I think we vastly undervalue the richness of the Great Lakes in a world where there’s a global scarcity of water,” Rockne said. “This is probably our single most valued resource in the United States, and once we pollute it with these types of chemicals, cleaning it up is something that just takes forever.”